Son of a Preacher Man

July 12, 2017

Categories: 10th Anniversary, Billy Graham, Franklin Graham

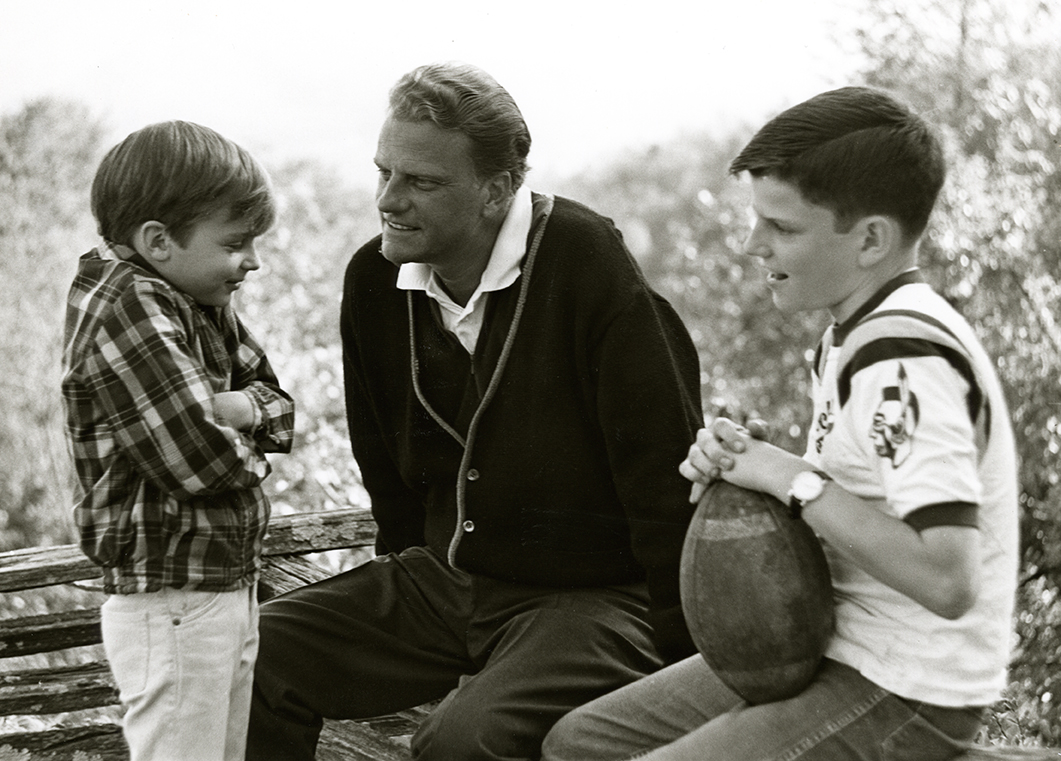

As the son of Billy Graham, Franklin Graham learned many lessons from his father. Read more about his journey from rebellion to reverend.

This article first appeared in WNC Magazine in 2007.

For all his youthful rebellion, Franklin Graham learned where he started—with family and the church—was where he always belonged

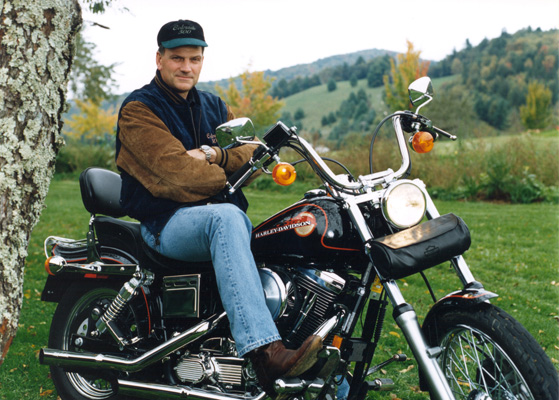

Fast cars. Fast motorcycles. Fast planes. “Anything that blows smoke and goes fast, I like it,” says Franklin Graham, son of world famous evangelist Billy Graham. His hankering for adrenaline-pumping experiences hasn’t changed even though he parted ways with the rebellious days of his youth and followed his father to the pulpit.

When he crisscrosses the globe on international relief missions, the [almost 65-year-old] Franklin buckles himself into the cockpit and pilots the plane to whatever destination he’s headed. “I’ve been flying for around 35 years,” he says. “Aviation is the one thing I learned in school that I use every week. We have 14 aircraft in the organization, and I fly all of them except the helicopter.”

Franklin maintains a hectic schedule of world travel for two organizations. In 1979, he became president and chairman of the board of Samaritan’s Purse, an international relief agency with corporate offices in Boone. There, he helps provide assistance to victims of natural disaster, war, disease, and famine in more than 100 countries. He’s also the CEO and president of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association—roles he took on in 2000 and 2001, respectively.

After serving God throughout the world, Franklin anticipates returning to his home, located on more than 100 acres in Boone, and his wife of 33 years, Jane Austin Cunningham Graham—a hometown girl he met when he was eight years old. It’s also the place where they raised their three sons, William, Roy, and Edward; and daughter, Jane Austin.

“It’s the only home my wife and I have ever owned. We were just kids when we first came up here to Boone,” he says. “I’ve lived all my life in Western North Carolina, and I can go anywhere in the world. But there’s something special when you land in Charlotte, and you see the mountains to the west.”

That notion, that he can be anywhere in the world but chooses to come back to the familiar, is a theme that runs through Franklin’s life—professionally, personally, and spiritually.

Franklin’s features are strikingly similar to his father’s, especially his magnetic eyes. On the day of this interview, he’s dressed in black jeans, purple shirt, and a black Harley Davidson ball cap. He looks more ready to jump onto a motorcycle than lead the faithful and help the needy.

His oversized office provides more insight into his personality and interests. It features an executive desk and conference table, along with a luxurious sitting area that resembles a living room decorated with the leather sofa and chairs and oriental rugs. Some of his hunting conquests—deer and elk—are preserved over the stone fireplace; Franklin has enjoyed the sport since he was a child. And antique guns are displayed on the walls. A multitude of family photos are showcased on the walls, as well as framed photos of his parents arranged on the bookshelves.

There were times in his youth when his choices and behavior gave his parents pause as they wondered about the direction their fourth child would take in his life. His teenage years were riddled with fights, cigarettes, and alcohol. In his book, Rebel With a Cause, Franklin writes: His parents “knew much more clearly than I did pressures I faced of being a ‘preacher’s kid’ as well as the oldest son of a ‘Christian legend.’ I’m sure God gave them wisdom to know that if they pushed me too hard to conform, I might take off running and never come back—not just away from them, but perhaps from God, too.”

His parents sent him to a boarding school—Stony Brook in New York—when he was 13. Enduring his freshman and sophomore years there, he then intensified efforts to persuade his father and mother, Ruth, to allow him to finish his studies at Owen High School near their home in Montreat. They finally agreed to a transfer following Christmas of his junior year. But he continued to be a handful and Owen’s principal quickly suspended him for fighting. Franklin also pushed the limits by staying out late and resisting wake-up calls to go to school.

His mother devised creative tactics to wake him, including stuffing a little firecracker under his door and crawling across the roof to knock on his window when he locked her out of his room. Her meddling made him “madder than a hornet,” but today he admires the spunk she showed and credits her for his bold spirit.

“Mama always had a sense of adventure,” says Franklin. “I remember one day there was a rattlesnake in the yard. She took a marshmallow fork and tried to pin the head of the snake down because she wanted to pick it up by the tail. I said ‘Mama, what are you going to do with that snake when you pick it up?’ She said she just wanted to pick it up. I don’t think she ever knew what fear was.”

Ruth wasn’t afraid to dish out tough love to her wayward teenager, but tensions continued to flair at Owen. The principal agreed to let Franklin finish his high school credits while attending LeTourneau College in Longview, Texas. “I did get a diploma from Owen, but I wasn’t there my senior year,” explains Franklin. “I think they threw the diploma at me.” When LeTourneau officials kicked Graham out for breaking rules, he returned home and spent two years at Montreat-Anderson College (now known as Montreat College).

Then in 1972, during a trip to Jerusalem, Graham underwent a personal transformation and committed his life to serving Jesus Christ. He writes, “that night I had finally decided I was sick and tired of being sick and tired. My years of running and rebellion had ended. I got off my knees and went to bed. It was finished.”

He believes the rebellion he experienced as a young man helps him relate to people he encounters through his ministry. “I went through a period of my life when I questioned and when I didn’t want God to be the Lord of my life,” says Franklin. “I wanted to be in control. I don’t think there’s anybody who’s ever lived who didn’t want to be in control. I found out that trying to be in control only messes things up worse. I think there are a lot of people who are where I was at one time. It just allows me to say, ‘Hey, I’ve been there. I know what you’re going through.'”

Franklin has witnessed much suffering during his missions for Samaritan’s Purse. He saw “bodies everywhere” and breathed in a “stench that was unbelievable” after a tsunami pulverized Thailand on December 26, 2004. He’s comforted people in war-torn countries, and he’s helped provide food and medicine to those suffering from dreadful diseases all around the world.

He recently talked with a man in Uganda who shocked him by saying he was thankful he has AIDS. Through his disease, and through the support of Franklin’s missionaries, the man found a relationship with Christ. “I’ve never had anybody tell me that before,” says Franklin. “It made me so grateful for our team of men and women who showed love and compassion for him.”

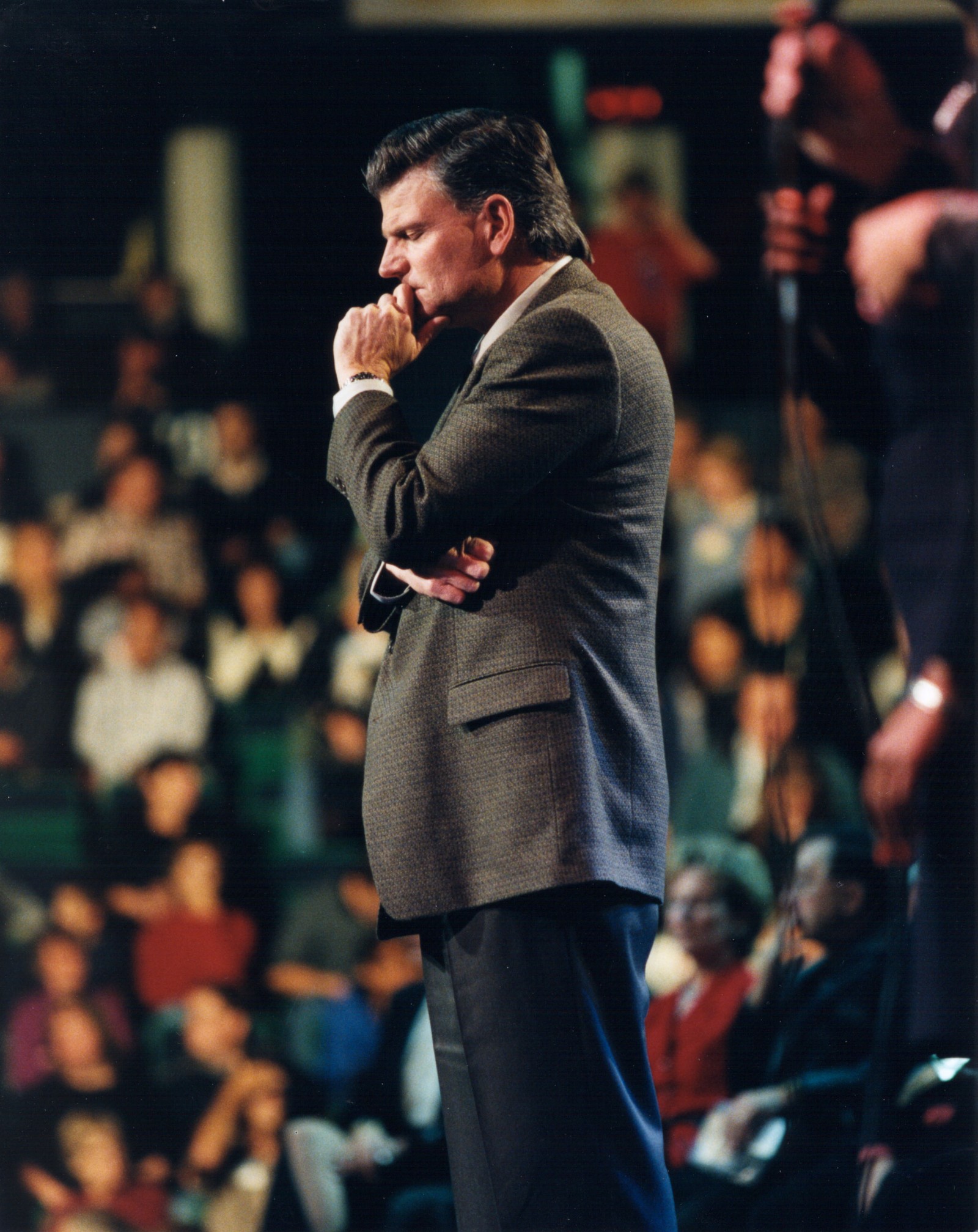

As Franklin has matured into his role as an evangelist, it’s common for people to compare him with his father. But they are separate individuals, with very different styles. “There’s only one Billy Graham,” he says. “There will never be another Billy Graham. My father and I are a lot different, but the Gospel that we preach is the same.”

Franklin is not the only grandchild to follow in his father’s footsteps; many of his close family members are involved in his work. All his siblings, including sisters Anne, Ruth, and Virginia, and his younger brother Nelson have a history of operating the family’s organizations. And Franklin’s two oldest sons, Will and Roy, have also chosen to serve in the ministry.

This year [2007] has marked a period of significant personal concern, celebration, and grief for Franklin. In March, his youngest son, 27-year-old Edward, suffered shrapnel wounds while serving in Iraq. Then, on May 31, Franklin was beside his father, who turns 89 in November, as he greeted a large crowd and three former presidents to officially dedicate the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte. This wonderful family celebration was followed by sorrow, as Franklin’s mother died, at the age of 87, just a few weeks later.

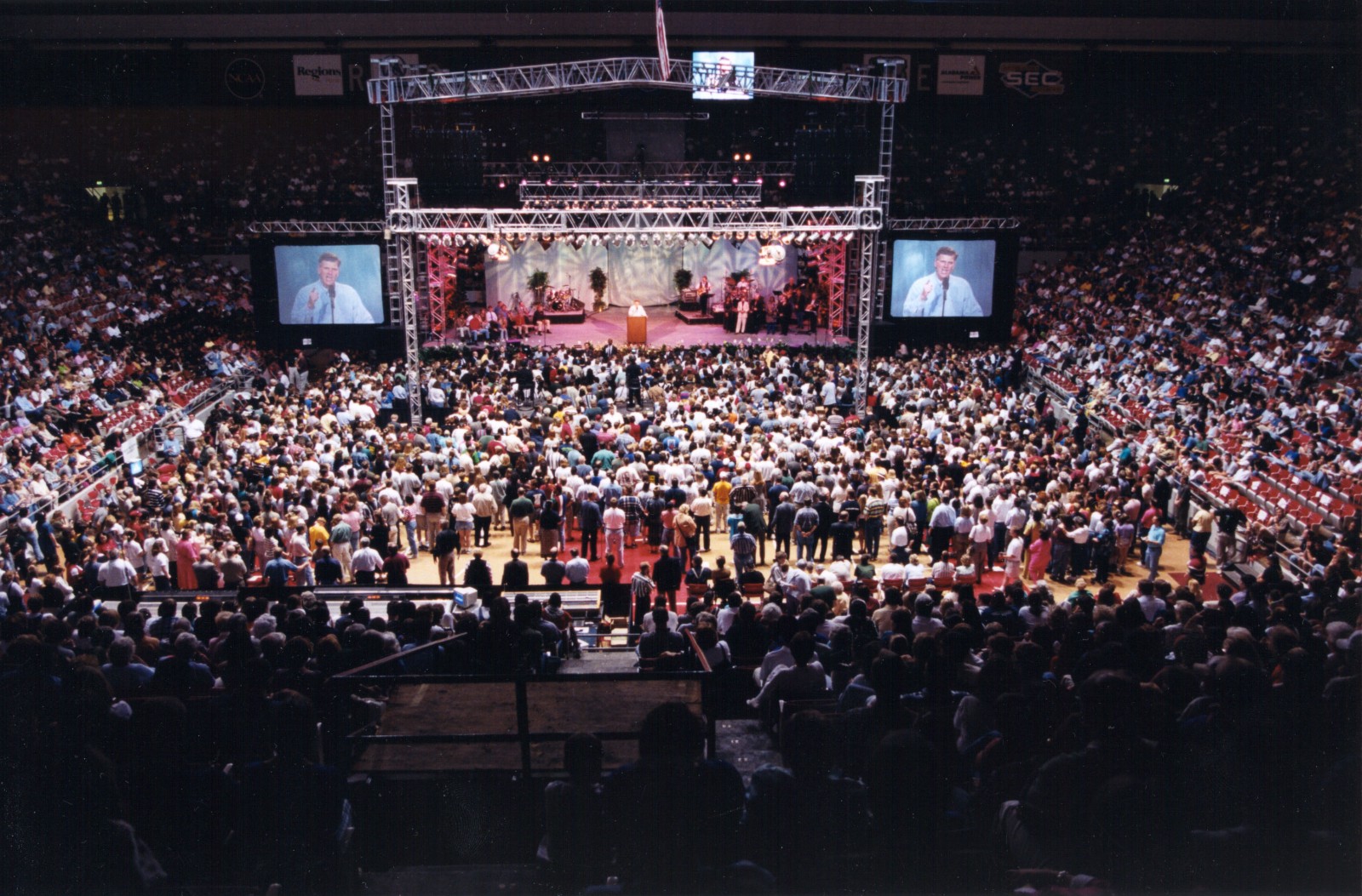

Today, Billy Graham is in declining health and no longer conducts his famous revivals. Instead, Franklin has taken on that role. He called the crusades “festivals,” and this year alone he’s preached to hundreds of thousands of people, both stateside and international venues such as Panama, Ukraine, Ecuador, and Korea.

If you were to ask Franklin where he gets the inspiration and the guidance to maintain such a large ministry and be involved in so many support efforts, the preacher in him would likely give credit to a source on high. But the direction he received from a family who never gave up on him is equally evident.